Great Powers, the Middle East and the Cold War

Introduction

The clash of great powers to control the Middle East, particularly between the U.S. and the U.S.S.R., neither began after World War II nor ended with the demise of the Soviet Union in 1991. Today, China, the U.S., Russia and Middle Eastern regional powers vie to influence everyday politics and resources. Treasured by foreigners, the region will remain coveted for centuries to come. The three major elements that have shaped Middle Eastern history for thousands of years will not disappear: its geographic location at the eastern end of the Mediterranean Sea, linking north and south and east and west; its historical place as the cradle to the three major monotheistic religions, where it has radiated an insatiable thirst by worldwide followers to assert presence and control; and the availability of the world’s largest known oil and gas reserves.

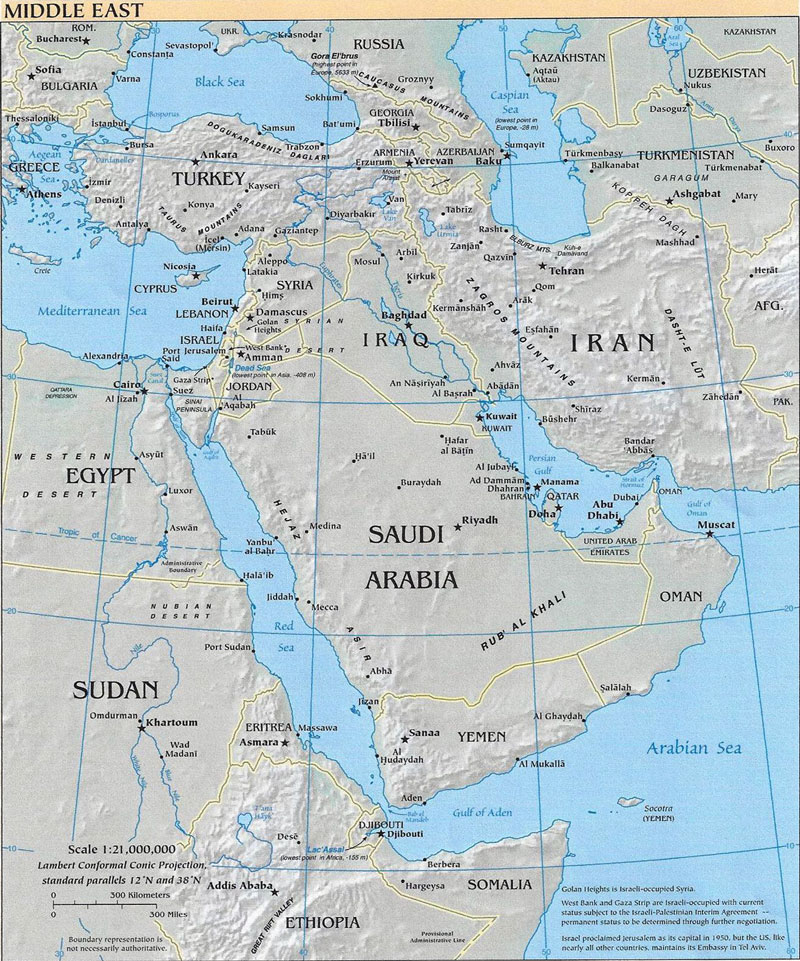

Historically, it was difficult to traverse the Middle East from north to south or east to west. Vast desert areas and mountainous zones blocked easy access to the region’s hinterlands. There were no multiple river and later railroad systems like the ones that shaped trade, development and politics in Europe and the United States. Instead, control of the key water passageways became critical for foreign powers: the Straits of Hormuz between Iran and Oman; the Bab al-Mandab Straits between Djibouti and Aden for access to the Red Sea; and the Turkish straits of the Dardanelles and the Bosporus, Russia’s pathway to the Mediterranean Sea. Likewise, dominance of the coastlines was strategically advantageous for local and foreign populations; control of the littoral areas from Gaza north to Latakia in Syria was of immense value. A string of two dozen Crusader castles hugged the coastline from Alexandretta in the north to Al-Arish in the south.

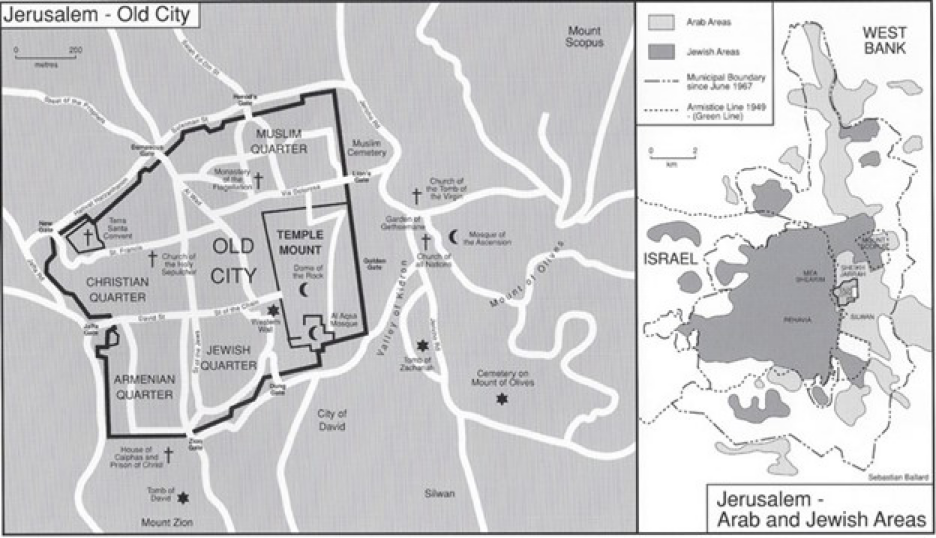

Once the Suez Canal opened in 1869 and the distance between London and the Arabian/Persian Gulf was reduced by 43%, its control was vital for sea traffic through the Middle East. Connecting South Asia and beyond to Mediterranean and Black Sea destinations, the canal accelerated already tense rivalries between European countries and Russia for influence throughout the Middle East. Spurred by secular leaders and religious zeal, European Christian Crusaders fought from the 11th to the late 13th century to control key holy sites in Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Nazareth and Capernaum, among others close to the Mediterranean coast. When Syrian President Hafez al-Assad explained to U.S. President Jimmy Carter in 1987 the meaning of a critical Crusader defeat near Jerusalem in 1187, he did not describe the European defeat as a success of Islam over Christianity, but as a victory of the Arabs over the West. Assad saw this military success not in religious terms, but in nationalist terms, a successful Arab defense against foreign intrusion. Ultimate sovereignty over Jerusalem with its religious significance remains an issue at the heart of resolving the Arab-Israeli conflict.

Singularly influential to the region’s history was the absence of water, with major exceptions — the Nile and Tigris-Euphrates river basins and some mountainous areas — as well as the extraordinary deficiency of cultivable land to sustain the region’s populations beyond subsistence agricultural work. Scarcity of cultivable land and water shaped the region’s political culture. Which tax farmers, families, tribes or dynasties controlled land and water determined who was in power and for how long. From the 1860s to the 1950s, those relatively few individuals dominated regional politics; these same elites often affirmed legitimacy for their local rule by collaborating with foreign powers. It happened in Egypt, Palestine, Iraq, Syria, the Arabian Peninsula and North Africa.

Twentieth century discoveries of oil and natural gas in exportable amounts markedly altered power structures within the Middle East. Oil-rich countries happened to be population-poor, and population-rich countries were oil-poor. Since the end of World War II, particularly after the October 1973 Middle East war, the dynamics of interregional politics swung heavily in favor of the oil-rich countries as they acquired vast wealth quickly. Those countries that sat on the largest known oil reserves in the world became highly prized targets for rich and poor countries with unquenchable oil thirsts. Oil availability also spurred interregional political backbiting and unending jealousies. Middle Eastern oil-exporting countries had enormous influence over oil market prices and a veritable endless supply of petro-dollars.

Modern imperialism and colonialism rekindled European and Russian strategic competition for access to and through the Middle East. In 1853, seeking to exercise protection for their Russian Christian Orthodox subjects under the rule of the Ottoman sultan, Russia was embroiled in disputes with France over control of Palestine’s holy places. As a result, the Crimean War erupted. Foreign engagement in the region grew as the French and British took interest in building the Suez Canal, culminating with British occupation of Egypt in 1881. In the last two decades of the 19th century, Germany steered its geopolitical and economic interests eastward into the Ottoman Empire in what was termed Drang nach Osten (drive to the East). Britain, France, Germany and Russia engaged in keen competition with one another for influence over the Ottoman Empire’s assets amid the empire’s slow demise during the first decades of the 20th century. Competition for access, trade and control of the eastern Mediterranean entwined with the Ottoman Empire’s unraveling, which evolved into the “Eastern Question.” The half-decade before World War I was essentially the first manifestation of the modern Cold War in the Middle East.

Beyond the Suez Canal, Britain expanded its quest for sway over not only Arab lands adjacent to it, but also lands as far east as the Persian Gulf, Afghanistan and across Arabia. From the late 19th century through the end of World War II, Britain negotiated dozens of agreements with Arab leaders, making alliances that assured British dominance of the Middle East. British officials were blunt about their intentions to dominate the Middle East. Lord Curzon, who became British viceroy in India, classified the Middle Eastern areas as “pieces on a chessboard.” D.G. Hogarth, later of England’s Arab Bureau in Cairo, called the Middle East an “intermediate land, a thoroughfare,” to be controlled. The French placed their cultural presence and strategic advance in the areas of North Africa, Lebanon and Syria.

With Britain and France victorious over the Ottoman Empire and its ally Germany in World War I, the stage was set for London and Paris to exercise virtually uncontested dominance over the former Arab provinces of the Ottoman Empire the next three decades. World War I was bookended by fierce public discussions and multiple secret agreements about trade, shipping access and land control in the Middle East, including the Suez Convention (1888), Constantinople Agreement (1915), Sykes-Picot Agreement (1916) and Montreux Convention (1936).

Seeking to secure port access and economic relevance, a strategic priority that extended from Catherine the Great in the middle to late 18th century to Vladimir Putin, Russian and Soviet leaders have perennially fought for access to and through the Dardanelles and Black Sea to the Mediterranean’s open waters. During the World War I period, Zionist leaders engaged with Russian counterparts to secure support for a Jewish homeland in Palestine, knowing of Russian strategic interest in the Middle East and offering themselves as friends to Russian leaders in return for support of a national home.

As World War II ended, the Cold War between the U.S. and U.S.S.R. raged across the globe, waged by proxies and allies in Southeast Asia, Africa, the Middle East and the Caribbean. It reached major points of direct great power confrontation during the 1962 Cuban missile crisis and teetered on the brink of a nuclear confrontation at the end of the October 1973 war. The Cold War during the second half of the 20th century was but a short moment in the long history of the Middle East, where outside powers fought for influence over what they considered essential strategic, economic and emotional needs.

In 1947, Soviet leaders regarded the forming Jewish state as a means to hasten British departure from Egypt, Palestine and other parts of the Middle East. Moscow endorsed the 1947 U.N. partition plan to create Arab and Jewish states in Palestine and recognized Israel immediately after its founding in May 1948. The U.S. State Department bluntly told President Harry Truman that it feared a Jewish state’s creation because so many of its recent immigrants from Russia might tilt favorably toward Moscow. With deep worry about a burgeoning Soviet-Israeli relationship, Truman dispatched a special envoy to Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion. Truman embraced Israel to be sure that it would align with American democratic values and remain engaged with America’s large Jewish population. Truman and his immediate successor, Dwight Eisenhower, both feared growing Soviet influence in the eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East. Both presidents issued strong presidential doctrines, Truman in 1947 and Eisenhower in 1957, urging containment of Moscow’s offensive forays around the world, particularly in the Middle East.

Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser chased the British out of Suez in 1956. By then, Moscow was providing Egypt with military, technical and economic aid. In 1958, when Nasser sought to influence Lebanese politics, Washington saw it as an overt attempt by Moscow to spread Soviet influence and a direct challenge to the Eisenhower Doctrine, which promised military or economic aid to any Middle Eastern country that resisted Communist/Soviet aggression. U.S. Marines landed in Lebanon in 1958 precisely to prevent Nasser from spreading Moscow’s influence there.

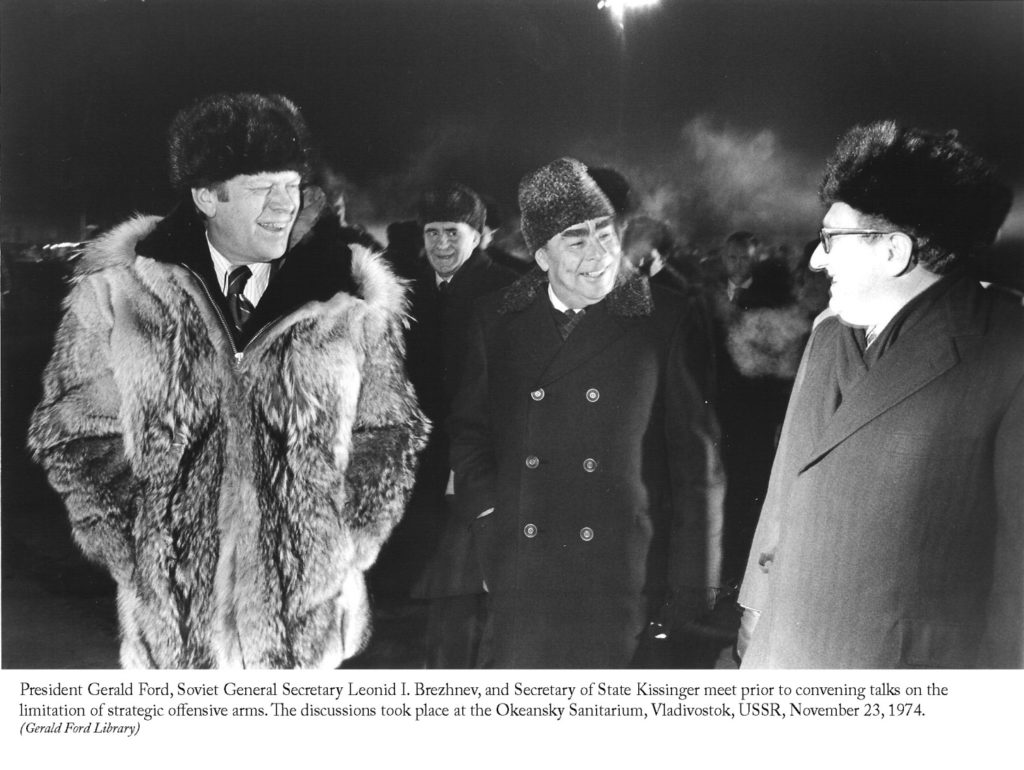

By the early 1950s, the Soviet Union had reacted to Israel’s alignment with the United States by establishing strong alliances and influence with Israel’s Arab neighbors, including Egypt, Syria, Iraq, Libya and numerous Palestinian organizations. Egypt, Syria and Libya possessed geographical advantages for the U.S.S.R. because each possessed potential and actual port facilities for Moscow’s fleets. By 1953, the Soviet Union cut diplomatic ties with Israel. Israel and the Soviet Union renewed relations under Nikita Khrushchev’s administration, yet tensions lingered. Israel engaged in numerous secretive missions to extract crucial Cold War intelligence for the United States. For Israel, from the 1950s forward, Moscow’s capacity for nefarious actions, aside from supporting a unified Arab world led by Nasser, represented the greatest physical threat to the Jewish state. Simultaneously, Washington grew closer to Israel because Arab leaders like Nasser refused to become U.S. allies. Moscow’s dominance over Eastern Europe shaped Israel’s acrimonious diplomatic relationships with those countries, apart from Romania and Yugoslavia, which charted their own courses with Jerusalem. Having pushed out the British, Nasser did not find it inconsistent to deepen his involvement with Moscow for two decades, until his successor, Anwar Sadat, sent the Soviets packing in 1972. Sadat turned to the United States for economic assistance and diplomatic engagement in finding Egypt’s way out of the conflict with Israel. Over several decades, until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Moscow provided vast quantities of weaponry and resources to Israel’s Arab neighbors. It openly supported Palestinian Arab terrorism against Israel and evolved into Israel’s greatest diplomatic adversary at the United Nations and other international forums. After the Soviet Union provided arms and military training to Arab states, used against Israel in the June 1967 war, the 1969-1970 War of Attrition and the October 1973 war, Israel feared Soviet intervention in these Arab-Israeli confrontations. Moscow choreographed the infamous 1975 U.N. resolution that defined Zionism as racism. Moscow again broke diplomatic relations with Israel after the 1967 war, not restoring them until 1991, just before the Madrid Middle East Peace Conference. Moscow’s perpetually fraught relations with Israel and an intentional U.S. policy to exclude Moscow kept the Soviets out of American-dominated Arab-Israeli mediation of the conflict. From the 1967 war, the United States took great pleasure that weapons supplied by Moscow to the Arabs were bested by arms provided in part by Washington to the Israelis. The Middle East, like other parts of the world, evolved into one of the Cold War’s tense and violent battlegrounds. Moscow and Washington each had friends, clients, proxies and competitions that survived the fall of the Soviet Union. During the Nixon and Ford administrations. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger developed a formidable relationship with the Soviet Union through a policy of détente, where Moscow and Washington strove to avoid clashing in a region that could lead into a nuclear confrontation, an outcome avoided during the last days of the October 1973 war.

The slow collapse of the Soviet Union catalyzed the Reagan administration but only temporarily diminished Moscow’s aspirations and appetite to maintain global influence. After the Soviet Union broke apart in December 1991, Russia’s strategic objectives for the region were the same as its predecessor state: access to and through the Middle East, warm-water ports in the eastern Mediterranean, and political and economic influence over parts of the region. As a major exporter of oil, Russia needed to influence pricing and production. For the second half of the 20th century, Moscow inserted itself into the Israeli-Palestinian dimension of the Arab-Israeli conflict. Russia still maintains pragmatic diplomatic associations with Hamas, Fatah, the Palestinian Authority, Turkey, Syria and Iran.

While Russia and Israel have similar interests in containing Iranian adventurism in Syria and elsewhere in the region, Russian President Vladimir Putin and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu strengthened ties diplomatically and personally but avoided stepping on each other over Moscow’s relationship with the Assad family until its fall from power in December 2024. Pragmatic engagement between the leaders reflects common interests. For Israel, engaging the Soviet Union even before the end of the Cold War had the strategic advantage of catalyzing the emigration of more than 1 million Jews from the former Soviet Union to Israel. Since the beginning of Israel’s history, the Moscow-Jerusalem relationship has been pragmatic; however, for most of Israel’s existence, Moscow has been an international diplomatic challenge and feared great power. Israel shed no tears when Moscow withdrew substantial military assets from Syria in December 2024.

The U.S.-Soviet Cold War in the Middle East contributed simultaneously to Israel’s national security and to its worst fears. In 1956 and again during the June 1967 war, Israel’s defense minister feared Soviet military intervention on behalf of the Egyptian army. During the War of Attrition over Suez, Israel shot down several Soviet aircraft, and Israel again feared Soviet intervention on behalf of Egypt at the end of the October 1973 war. Moscow’s alliance with Arab states from the 1950s through the 1980s strengthened Washington’s embrace of Israel as a trusted ally, friend and ultimately strategic partner. The United States became the key Arab-Israeli negotiating mediator, essentially Israel’s lawyer in many of the negotiations that unfolded. The Cold War thus greatly contributed to the United States becoming Israel’s most important and constant source of economic aid, military supplies and international diplomatic support. And the U.S. gained enormously from shepherding Egyptian-Israeli peace through Cairo’s 180-degree turn from Moscow to the Washington, which Peter Rodman, who worked in Kissinger’s State Department, called “the greatest success for the United States in the Cold War.”

Smoldering embers of the Cold War remained and grew during the first quarter of the 21st century as individual Middle Eastern countries generated relationships with the historic great powers, with China added to the mix. The region’s vast energy resources, strategic waterways and geopolitical instability, the same things that drew the great powers to the region in the 19th and 20th centuries, have drawn the competing interests of the United States, China, Russia and European powers. These powers have, as in the past, cultivated alliances, patrons and proxies with countries and individuals, often backing opposing sides in conflicts while vying for economic, military and ideological influence.

The Cold War in the Middle East (2000-Present): Great Power Rivalries

Since 2000, the Middle East has remained a key battleground for global powers, resembling a modern Cold War dynamic, with the U.S., China and Russia maneuvering for influence. Far and away the most stable and longest-lasting relationship is that of the United States and Israel, perhaps the deepest and most interconnected of any U.S. relationship other than that with Great Britain.

Notably in 1979, the U.S. lost Iran as an ally, with Tehran becoming Washington’s most vocal and active detractor in the region. On the other hand, along with Israel, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Egypt and Jordan have remained steadfast allies. After 9/11, U.S. military interventions in Afghanistan (2001) and Iraq (2003) reshaped the regional order. Washington sought to counter terrorism and prevent nuclear proliferation, particularly regarding Iran, but has not thwarted Iran’s drive to become a nuclear power for regime protection. American credibility was not enhanced by the prolonged wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

China expanded its economic footprint into the Middle East as part of the greater need to ensure oil import security. It did so by steadily expanding its Belt and Road Initiative, investing in Middle Eastern infrastructure, energy and technology. It maintains strong economic ties with Iran, purchasing oil despite U.S. sanctions, and has deepened relations with Saudi Arabia and the UAE. Unlike the U.S., China maintains a non-interventionist approach, positioning itself as a neutral economic partner. In 2023, Beijing brokered a historic détente between Saudi Arabia and Iran, highlighting its diplomatic ambitions in the region.

Russia’s military and diplomatic resurgence appeared with its 2015 military intervention in Syria, supporting Bashar al-Assad’s regime against U.S.-backed rebels. Moscow cultivated relations with Iran, supplying military aid and cooperating in Syria. Russia maintains energy and arms deals with Saudi Arabia and the UAE, balancing ties despite backing opposing factions in conflicts like Libya. The war in Ukraine has further shaped Russian policy, deepening Moscow’s reliance on Middle Eastern allies for economic and diplomatic support.

Russia has since the 1990s forged a deep strategic partnership with Iran, driven by mutual opposition to U.S. influence in the Middle East. Their cooperation spans military, economic and diplomatic spheres, with both nations backing Syria’s Assad regime, opposing Western intervention and circumventing U.S. sanctions. Militarily, Russia supplied Iran with advanced weaponry, including the S-300 air defense system, delayed from 2007 and delivered in 2016, though rendered useless by Israel’s destruction of Iran’s air defenses in October 2024.

In Syria, Russia and Iran worked closely to keep Assad in power, with Moscow providing airpower and Tehran deploying its Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps and proxy militias such as Hezbollah. With Israel’s decapitation of Hezbollah’s leadership and fighting force and Assad’s fall in 2024, Russia reduced its presence in Syria, but its need to be politically present in the eastern Mediterranean has not dwindled since Catherine the Great. How post-Assad Syria is configured in terms of foreign alliances will be telling for how deeply Moscow will again seek its space in Syria. Turkey, the Saudis and the U.S. have opportunities to limit Russian and perhaps Chinese roles in Syria’s future.

Finally, China’s strategy in the Middle East remains centered on economic pragmatism, avoiding direct military conflicts while increasing influence through trade, investment and diplomacy. Beijing’s relationship with Iran and the Gulf states will be telling for Russia and the U.S. Any diminution or expansion of Iran as a regional power also will be notable. China has steadily strengthened ties with Iran, primarily driven by energy needs and opposition to U.S. dominance. China remains Iran’s top oil buyer, often defying U.S. sanctions. The 2021 China-Iran 25-year agreement promised $400 billion in investment across sectors, though much of it was slow to materialize. In security cooperation, China has avoided direct military alliances. It engaged in naval drills with Iran and Russia, signaling solidarity against Western hegemony and a geopolitical pragmatism while seeking and evolving good relations with Iran’s rivals, particularly Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

In the Gulf, China has cultivated strong relations with monarchies, leveraging economic diplomacy and avoiding regional entanglements. In the past 10 years, China has overtaken the U.S. as Saudi Arabia’s largest trade partner, investing heavily in infrastructure and technology. With the UAE, China seeks tech investments, particularly in AI and 5G, despite U.S. pressure to limit Chinese influence. With Qatar, Beijing secured long-term liquified natural gas deals, ensuring stable energy supplies amid global uncertainty.

Differences and Similarities Between the Cold War Periods

Differences and similarities are apparent in the 2000-2025 period in substance and ideology. First, unlike the U.S.-Soviet Cold War from 1945 to 1991, which was strictly a bipolar contest, today’s Middle East rivalry involves multiple global powers — the U.S., China, Russia and Europe — each with distinct interests and strategies.

Second, the original Cold War was defined by capitalism vs. communism. The modern Middle Eastern Cold War is driven by economic and geopolitical competition rather than ideological rivalry. The U.S. promotes a neoliberal order, China champions state-led capitalism, and Russia pursues resource-driven influence.

Third, during the Cold War proxies were largely controlled by superpowers (e.g., Soviet-backed Egypt, U.S.-backed Saudi Arabia). Today, Middle Eastern states such as Saudi Arabia, Iran, Turkey and the UAE have more autonomy and play great powers against one another to maximize their own interests. Iran, engaged in promoting its radical Islamic ideology in the region and elsewhere, including Latin America, cultivates deep associations with China and Russia in shaping oil prices and in reliance from both of those states and from North Korea for technology and military supply.

Fourth, while the U.S. maintains military alliances (NATO, the work of the U.S. Central Command), today’s competition is also fought through economic influence (China’s Belt and Road), cyber operations and control over digital infrastructure (5G, AI). Instead of military blocs, we see economic zones shaping alliances.

Fifth, the original Cold War was deeply tied to oil geopolitics, but today’s Middle East Cold War is shaped by the transition to renewable energy, technological investments and artificial intelligence. China’s dominance in clean energy and electric vehicles, coupled with Saudi and UAE investments in post-oil economies, adds a new dimension to global competition.

— Ken Stein, February 10, 2025