Go to The Timeline starting at Era II

Autonomy to Sovereignty

From 1898 to 1948, Zionism evolved from an idea to a concrete reality: the actual establishment of the Jewish state, Israel. When Herzl wrote his idea for The Jewish State, Jews had little political power, and almost no financial resources with which to bring the Zionist idea to fruition. Jews had remained steadfast in their communal commitment to preserve their identity. They also had experience in lobbying others to achieve political and economic objectives. Whether or not Zionists achieved permission or protection from a country or leader, Jews continued to immigrate to Palestine. Slowly, they created facts by linking people to the land. For the next half century, fortuity and fortitude made the Zionist undertaking a reality. Several interconnected reasons explain Zionist success in creating a state; each was necessary for the establishment of Israel as a Jewish state.

The most significant reasons were:

- Foresight, pragmatism, and improvisation of Zionist leaders

- The manner in which Eretz Yisrael (later termed Palestine) was governed during the Ottoman, and later British mandatory times

- The socio-economic demography and political behavior of the Arab population in Palestine, and that of Arab leaders in neighboring states

- Events outside of Palestine that catalyzed the state’s establishment

Engaging Ottoman Rule and the Arab Countryside

When the state of Israel was declared on May 14, 1948, the Jewish population had increased from 30,000 in 1900 to over 650,000. By the time Hitler invaded Poland in September 1939, 420,000 Jews were living in Palestine, and three-quarters of land that Jews would purchase to create a nucleus for a state was already in Jewish possession. Unquestionably, a Jewish state was in the making before the Holocaust unfolded. Palestinian Arab newspapers from the 1930s tell us that many Arabs had become aware of that reality as well. Undoubtedly,the catastrophic events of World War II catalyzed the Jewish state’s creation— but the organizational and institutional development, strategic planning, and ground work for Israel’s establishment took place well before it was known that six million Jews had perished at the hands of Nazi Germany. Jews had learned from excruciating and repetitive experiences of degradation that gentile indifference to Jewish suffering was pervasive. The inability and unwillingness of non-Jews to thwart Nazism’s march sharpened Zionist determination to build a state in order to protect Jewish life and property.

If Zionists had tried to build a state in an area with a history of efficient public administration, or local or regional political institutions capable of resisting Zionist efforts, the Zionist idea would simply have not have become a reality. The Ottoman Empire’s administration of the Middle East, including the area of Palestine (the area west of the Jordan River), was lax, inefficient, and beset by corruption. The majority of the local Arab population was rural, illiterate, impoverished, inefficient in its modes of cultivation, and constantly subject to the abuse of a privileged class of tax farmers, money lenders, and notables. Arab social elites had a standard of living not enjoyed by the poor and perennially indebted rural peasantry. Many notables chose to maintain that standard of living by selling portions of their land to Zionist purchasers. Many others did not, staying true to their Arab communal identities. Much of the land in the region, in fact more than half of all of Palestine’s geographic area, was inhospitable and not suitable for cultivation. Fertile lands were controlled by a few who bought and sold land to make financial profit. Three times during these fifty years, Palestine’s rural economy was devastated; first by the massive destruction of trees, crops, and live-stock that resulted from a disabling locust plague and fighting between Ottoman Turks and the British during WWI; second, by drought and poor harvests in the early 1930s that led to severely declined crop yields; and third by the 1936-1939 Arab rebellion against the British and Zionists. After the rebellion, a good portion of Palestine’s rural country-side, beset by violence, was left with destroyed villages, uprooted crops and trees, damaged harvests, and rural terrorist bands extorting food and supplies from an already economically drained population. In the wake of such ravages, the Arab community in Palestine possessed little economic strength to recoup, let alone to challenge Zionism’s slow but consistent growth.

The World Zionist Organization’s founder, Theodor Herzl, died quite unexpectedly in 1904. Herzl’s untimely death set a precedent that would be repeated for the next hundred years: the movement outlasted the loss of a talented leader. Zionism, and later Israel, possessed a vast array of persistent individuals who grasped the leadership standard and drove the movement forward.

After Herzl’s death, Zionist leadership passed to Max Nordau, Chaim Weizmann, Rav Avraham Kook, Vladamir Jabotinsky, David Ben-Gurion and dozens of other individuals.

All the while, several thousands of Jewish immigrants arrived in Palestine with varied skills, some capital, and a commitment to build a new home for themselves. Some who came did not like the new experiment in rustic and often harsh living; many left Eretz Yisrael and abandoned their attempt at the Zionist experience.

As their ancestors had done in Europe centuries earlier, Zionists created communal institutions to meet immediate needs. The Jewish National Fund, Jewish Colonial Trust (a bank), Palestine Office of the World Zionist Organization were all established to assist the growth of the Zionist project.

Managing the British Administration

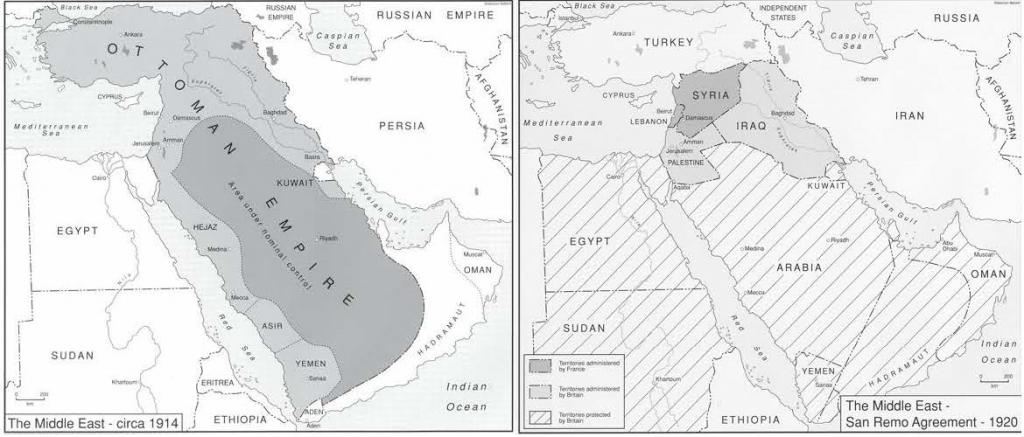

Before the end of World War I, Jews had already lobbied the Ottoman Empire, Great Britain, and other powers to affirm a political right to grow Jewish presence in Palestine. The Ottoman Sultan said no, yet in small numbers Zionists immigrated and bought land there anyway. Ensconced in India, Burma, and Aden since 1858 and in Egypt since 1881, Great Britain made dozens of alliances and agreements with regional Arab and Middle Eastern leaders— all aimed at assuring an exclusive British right to create and sustain a contiguous land bridge from the strategically critical Suez Canal in Egypt eastwards to the Persian Gulf and Indian Ocean. D.G. Hogarth, Secretary of State for India and later a member of Britain’s Arab Bureau in Cairo, called the Middle East “a thoroughfare…the communication between the West and the West-in-the East.” To that end, Britain made numerous promises to Arab leaders seeking their support in the war against the Ottomans. Across the Middle East, including Afghanistan and Persia, they consolidated bi-lateral relationships and their presence through alliances, declarations, treaties, and understandings that began well before the war and continued for decades thereafter. Particularly, they supported Hashemite, Kuwaiti, Qatari and Saudi families’ rights to local rule. The British secretly negotiated and signed the 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement with France and other powers, with the objective of physically controlling or influencing the policies of leaders in the soon-to-be-former Arab territories (Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, Jordan, and Palestine) of the Ottoman (Turkish) Empire. The 1917 British promise to the Jews in the Balfour Declaration to facilitate the development of a Jewish national home in Palestine fit most conveniently into Britain’s geopolitical plans. The 1935 opening of the Iraqi oil pipeline terminus at the Palestine port of Haifa even further elevated Palestine’s strategic value for the British— particularly its navy, which was switching from coal to oil power. The Zionists and the British developed a symbiotic relationship. The Zionists wanted to develop their national home in Palestine and of course did not mind that the process of doing so fell under British protection. As for the British, they wanted a friendly group who would support British strategic interests in Palestine.

After World War I, the Middle East was in economic and administrative turmoil. Its political future was determined by primarily Western Powers. The area of Palestine fell to British military forces in December 1918. Two years later, the British established their civil administration there and in Iraq. Simultaneously, in 1920, the French set up their administration in Syria and created Lebanon as a predominately Christian state. In 1922, the League of Nations Mandate for Palestine reaffirmed the British right to govern Palestine, which specifically stipulated the development of the Jewish national home (according to the 1922 HMG White Paper) in line with the “economic capacity of the country to absorb new immigrants.” A Jewish Agency was recognized as the official Zionist representative entity to the British administration in Palestine. The proposed establishment of an equivalent Arab Agency was rejected by the Palestinian Arabs. Zionists were delighted to have international legitimacy granted by the British and then by the League of Nations. Both sanctioned the Jewish/Zionist right to build a homeland. The British saw it as a homeland; the Zionists viewed it as a state-in-the-making. They erected educational institutions (such as Bezalel, the Technion, and the Hebrew University), created the Histradut (labor) and Haganah (defense) organizations, founded democratic institutions like the Va’ad Leumi, and developed a highly sophisticated Jewish Agency to plan for Jewish immigration, land settlement, and local defense needs. In addition, they regularly interacted with the British, the League of Nations, and, later, the United Nations. Predictably, the Palestinian Arab political elite and majority rural population were angered and agitated by all aspects of developing Jewish statehood. When British policy deviated from Zionist objectives (as it did often) and threatened to stop the national home in general (as it did with the 1939 White Paper), Zionist leaders protested, but worked around whatever restrictions were applied to them. Yet the Zionists remained allegiant to Great Britain for her protection. In refusing to accept Zionist presence, the Palestinian Arab leadership consistently also boycotted engagement with the British because London did not halt or reverse Jewish growth. The Palestinian Arabs’ fierce refusal to participate in any governmental process that might imply recognition of Zionism was evidenced by Mufti Hajj Amin Al Husyani’s Decision to reject the 1939 White Paper. With his rejection of the White Paper, the Mufti declined the opportunity to establish a a majority Arab state in all of Palestine– in spite of his advisers and many fellow Arab notables.

Building the State's Infrastructure

The damage the Palestinians sustained from refusing to accept Zionism or British presence was not only philosophical— it had political consequences, too. By choosing official boycott, the Palestinians Arabs hurt themselves and snubbed many British officials in Palestine who were unreservedly sympathetic to their cause and to their clear opposition to Zionism. By choosing to remain aloof from engagement with the British administration, Palestinian politicians forfeited the ability to shape the content of local regulations, laws, and ordinances that affected daily life in Palestine. Their persistent refusal to provide evidence or testimony before British and UN commissions of inquiry that looked into the future of Palestine greatly hampered the airing of Palestinian views. This was a conscious choice on the part of Arab leadership.

For their part, the Zionists gladly configured their national home under Britain’s physical protection. The Zionists developed political autonomy, settled Jews, built schools and small industries, and made strategic decisions on how and where to grow their state. In 1937, the Jewish National Fund produced an assessment of land purchase possibilities that would greatly aid Jewish land holdings: The Political Significance of Land Purchase. It was the good fortune of the Zionists that they were able to grow a viable economic and political infrastructure without having to devote time and manpower to the defense of Palestine’s borders against foreign invaders.

As they did in governing Iraq in the same post WWI period, Britain gladly used locally generated tax revenue to support their imperial presence. Their spending priorities included roads, ports, highways, and military installations, all aimed at securing Palestine strategically. Imported Zionist capital indirectly helped fund public work projects – and Arab employment throughout the Mandate. Jewish presence helped stimulate better health care for Arabs and Zionists alike. By 1936, though the Zionists were less than a third of the total population, they contributed more than 50% of British revenue there. Evidence from multiple scholarly and archival sources suggests that the nucleus for a Jewish state was present in 1939. Even British officials that opposed Zionism suggested the separation of the two communities by geographic partition.

A destitute Arab peasantry, along with a socially and politically disjointed Arab leadership, left Arab Palestinian society simply unequipped and broadly impoverished to mount any serious challenge against the Zionist commitment to create a state. In July 1937, the Peel Commission Report suggested that Arab and Jewish communities could not live together. It proposed a separation the two populations, and the creation of a state for each of them. Ultimately the British withdrew this idea, in part because the Arab state would have been economically non-viable. Instead the British issued the May 1939 British White Paper on Palestine, which dramatically truncated the Jewish National Home’s growth through severe restrictions on Jewish immigration and Jewish land purchase.

Despite the restrictions, Jews continued to immigrate in small numbers to Palestine and Arabs continued to sell land to willing Jewish buyers. British Colonial Office officials whose sympathies sat with the Arabs of Palestine noted in 1939 and 1940, “we need not have too much sympathy with the Arabs who make a practice of selling lands to Jews…the Arab landowner [needed] to be protected against himself.”

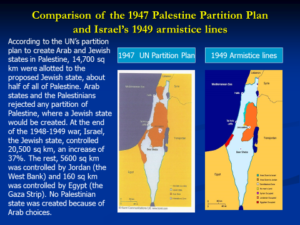

At the end of the 1930s, with disaster looming in Europe, the Zionists remained steadfast in taking control of their own destiny, however limited it was at the moment. David Ben-Gurion, as head of the Jewish Agency, decided to build support for Zionism among the large American Jewish community (which was still mostly apathetic in regard to Zionism). In 1942 he announced the Biltmore Program in New York, which avowed the intention to create a Jewish state in Palestine. It was not a great secret, but Ben-Gurion sought to galvanize American Jewry to support Zionism. He understood the political impact that Jews could have within a democracy. Meanwhile, the Palestinian Arabs remained torn by parochial interests. Leaders in surrounding Arab states cared little for the Palestinians themselves. Egypt and Jordan were at odds with one another about who would take Palestinian land when the Zionists would be defeated. Egypt’s King Farouk and Jordan’s Emir Abdullah were incessantly at odds with one another about Palestine’s future. Surrounding Arab states made it clear in September 1947 that they wanted no compromise with Zionism or the establishment of a Jewish state. Arab League Secretary General Abdulrahman ‘Azzam Pasha rejected any compromise with the Zionists. Meanwhile in Europe, Jewish officials smuggled about 100,000 Jewish survivors from the war into Palestine, circumventing the British blockade against Jewish immigration. At the United Nations in San Francisco and then in New York, Zionists lobbied intensely to have UNGA Resolution 181 Partition Plan passed. The Zionists wanted the international community to sanction the establishment of two states in Palestine. The Zionists did not want either Great Britain or the United States to govern Palestine as another mandate or trusteeship. In Palestine, the Jewish Agency secured what few weapons and ammunition they could for the inevitable coming war with local Arabs and surrounding Arab states. Zionist diplomats succeeded in persuading others of the justice of their cause, despite decades of anti-Semitism and deep opposition to a Jewish state, prevalent in key pockets of the US State Department and the British Foreign Office. Meanwhile, Jews in Arab lands around Palestine increasingly felt the anger of populations and governments hostile to Zionism. Jewish institutions and living quarters were attacked, forcing many Jews to immigrate. Many would end up in the new state of Israel.

For a synopsis of the “The 1947-1949 war,” please see (https://israeled.org/the-arab-israeli-war-of-1948-a-short-history/)