From biblical times to the present, Jews and Judaism have had an unbroken connection to Zion, a reference to Eretz Yisrael, the Land of Israel, derived from the hill at the heart of Jerusalem. Zionism was and remains the Jewish quest to have and sustain a Jewish state in Jews’ ancient land. Zionism is Jewish nationalism.

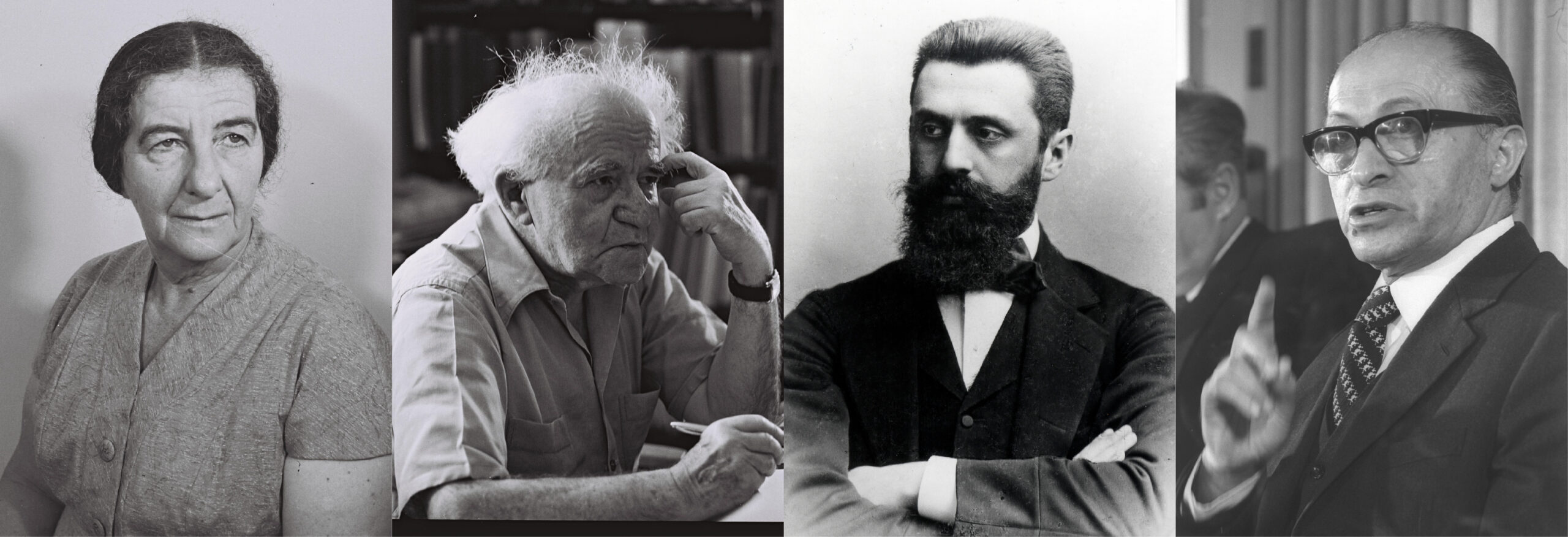

A relatively small number of Jews who decided to control their own futures by seeking, making and keeping a state wrote the story of modern Israel. Linking people to the land and building an infrastructure for a state are the story of modern Zionism, the story of Israel’s establishment.

The key outline for re-establishing the modern State of Israel is found in Theodor Herzl’s answer to “the Jewish Question” in The Jewish State. The Balfour Declaration and Israel’s Declaration of Independence are the other basic documents that chronicle the half-century effort to re-establish a Jewish territory in the ancestral Jewish homeland.

The Origins of Zionism

Modern Zionism did not begin with Herzl’s life or his writings, though he did give it form, organization and a plan of action. For the origins of Zionism before the late 19th century, we suggest the 1906 entry on “Zionism” in The Jewish Encyclopedia, keeping in mind that the ideas of Jerusalem and Zion were part of the very foundation of Jewish people going back to the Torah that initiate Jewish identity from Judaism’s birth.

Herzl, as the catalyst of modern political Zionism, had little connection to Judaism. By the 1890s, his work increasingly exposed him to antisemitic rhetoric, that he saw firsthand in covering the Dreyfus Trial in 1894, where a French Jewish officer was erroneously accused and found guilty of selling secrets to others. The widespread antisemitism he witnessed convinced him that assimilation would not protect Jews, leading him to advocate for a Jewish state as the only solution to the “Jewish question.”

In 1896, Herzl published Der Judenstaat (The Jewish State), outlining his vision for a sovereign Jewish nation to escape persecution and achieve security. This work galvanized Jewish communities worldwide, communities that already had been churning about whether they should remain orthodox in their beliefs, which included waiting for the Messiah to better their lives and return to Zion. In essence, Herzl motivated others to take destiny into their own hands, and not wait for prophetic intervening.

From Herzl’s writing and choreography of bringing like-minded Jews together, and it must be noted that the number of Jews who began to embrace Zionism or reconnecting physically with their ancient homeland were a tiny fraction among Jews worldwide. Zionism was a minority movement among Jews at the time that saw millions rather than several thousand moving to Canada, the US, South Africa, Australia, South America, and elsewhere.

From Herzl’s leadership, Jewish organizations were born that supported the slow growth of Jewish presence in Eretz Yisrael, variously also titled, the Holy Land, or Palestine. Zionism’s goal of having again a territorial scaffolding for Jewish life was a common view held by adherents, but their multiple ideological avenues that Jews felt should be taken to reach the objective. Philosophical diversity ranged from political action to waiting to receive permission to immigrate, from Zionism only being a Jewish cultural center to one that should be dominated by socialism, capitalism, secularism, or modern orthodoxy.

For an excellent, recapitulation of Zionism in the years before the state’s establishment, we recommend “The Zionist Movement,” which includes the history of Palestine, in the Israel Yearbook, 1950-51.

To understand how the Zionists connected Jewish immigration to land purchased in Palestine, we present Forming a Nucleus for the Jewish State (also in Hebrew and Spanish).

For a video overview of the connection among the Jewish people, the Land of Israel and a Jewish state, watch or listen to CIE President Ken Stein’s 33-minute presentation on “Jewish Peoplehood, Zionism and State Building.”

Support for Building a Jewish State

The 19th century plan to rebuild a Jewish state required a population and a place, which was Eretz Yisrael, the Holy Land, called Palestine by the Great Powers after World War I. As for the population, Jewish identity, antisemitism and the failure to find civic equality in Europe catalyzed Jewish immigration to democratic settings and support for the option to build a Jewish state. The Jewish population in Palestine increased from 25,000 in 1882 to 600,000 in 1948, with 400,000 Jews in Palestine by 1940. Jewish land ownership grew from 450,000 dunams (a dunam was a quarter of an acre) to 1.4 million dunams in 1940 and 2 million by January 1948. To understand how Jewish immigrants reconnected with the land, how they purchased small areas of land from Arab owners, and their interaction with the British as the administrators of Palestine after World War I, see Zionist Land Acquisition: a core essential in establishing Israel – The pace of physical and demographic growth over that nearly 70-year period was steady but uneven. Jewish immigrants were able to establish contiguous territorial areas partly because an impoverished peasantry, burdened by centuries of debt, and elite politicians, motivated by the potential for massive profits from land sales, alienated enough land to allow Zionists to piece together the territorial nucleus that eventually became Israel.

Charting the geographic placement of the 315 Jewish settlements built in that period unfolds the footprint for the state and provides an easy visual explanation for the United Nations’ proposed borders in its 1947 Partition Plan, also known as the UNGA Resolution 181.

In the decades leading up to 1947, Jews and Arabs increasingly chose to live apart, and repeated outbreaks of violence between the communities highlighted the need for separate Jewish and Arab states in Palestine, with Jerusalem under international administration. This opposition to a Jewish state and compromise with Zionism was exemplified in a conversation the Arab League had with three Zionist leaders in September 1947. During this meeting, Azzam Pasha, the head of the Arab League, declared, “No compromise with the Jews was possible, and it might be that we Arabs will lose Palestine, but war with you is our only option.” Arab leaders rejected the partition plan, and the Palestinian Arabs were denied independent representation, as their agency was effectively usurped by Arab leaders and states. The UN resolution provided a crucial legal framework for the eventual establishment of the State of Israel.

The groundwork for international support and legitimacy for Jewish homeland building was laid decades earlier through the League of Nations’ Mandate for Palestine (1922), which tasked Britain with facilitating Jewish immigration, land settlement, and self-governing institutions while protecting the rights of all residents. Together, these milestones underscored the global recognition of Jewish self-determination, enabling the transformation of the Jewish population in Palestine into a viable state by 1948.

The Creation of Israel

The creation of Israel was formalized on May 14, 1948, with the Declaration of Independence, which proclaimed the establishment of a Jewish state in Eretz Yisrael. This declaration highlighted the historical connection of the Jewish people to the land, the support of international legal frameworks such as the UN Partition Plan, and the imperative for a homeland following the atrocities of the Holocaust. The newly declared State of Israel sought recognition from the international community and was admitted to the United Nations on May 11, 1949, under UNGA Resolution 273, which acknowledged its statehood and commitment to peace and equality for all its inhabitants. Further solidifying its identity as a refuge for Jews worldwide, Israel enacted the Law of Return in 1950, granting every Jew the right to immigrate and gain citizenship. These foundational steps ensured Israel’s emergence as a sovereign state dedicated to Jewish self-determination and democratic principles.

Documents

Biblical Covenants

Liturgical References to Zion and Jerusalem

1893 Andrew D. White on the wretched Jewish Situation in Russia

1896 Herzl – The Jewish Question and the Plan for the Jewish State

1897 Max Nordau, Addresses the First Zionist Congress, Basel, Switzerland

1906 “Zionism.” In The Jewish Encyclopedia

1917 The Balfour Declaration

1922 League of Nations – International Legitimacy granted for creating a Jewish National Home

1937 British Peel Commission Report recommends an Arab and Jewish state

1938 Chaim Weizmann Rallying World Jewry to Partition of Palestine – two states

1942 David Ben-Gurion, The Biltmore Address – a Jewish state is at hand

1945 A Collection of Reasoned Views for the Dysfunctional Condition of the Palestinian Arabs’ Political State of Affairs

1947 Abdulrahman ‘Azzam Pasha Rejects Any Compromise with Zionists

1948 Israel Declaration of Independence

1949 Admission of Israel to the United Nations

1950 Israel’s Law of Return