Assembled here are key sources that have shaped the modern Middle East, Zionism and Israel. We have included items that give texture, perspective and opinion to historical context. Many of these sources are mentioned in the Era summaries and contain explanatory introductions.

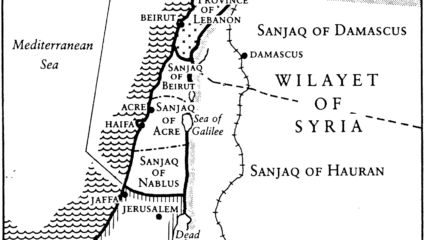

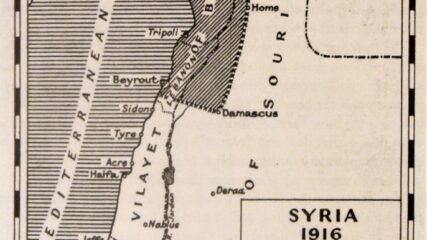

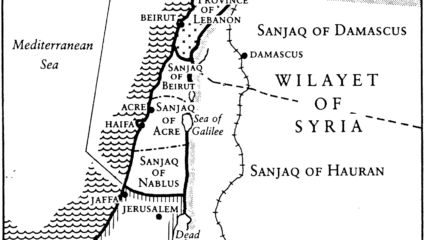

The Sharif of Mecca and Sir Henry McMahon, a British official in Cairo speaking for the Foreign Office, exchange letters about the current war effort against the Turks and the future political status of specific Arab lands in the Ottoman Empire. McMahon says, as he repeats in 1937, that the area of Palestine is excluded from any area to be provided to an Arab leader after World War I. The British instead allow the area of Palestine to develop as a “national home for the Jewish people.”

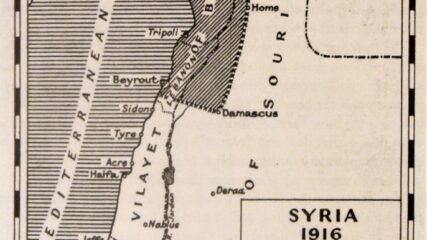

Britain and France secretly divide the Arab provinces of the reeling Ottoman Empire to meet their own geopolitical interests. They offer no concern for the political aspirations of indigenous populations.

The British Foreign Ministry promises to work toward a Jewish national home in Palestine with no harm to non-Jewish populations or to Jews living elsewhere who might want to support a Jewish home.

Herbert Samuel, soon to serve as Britain’s first high commissioner for Palestine and the only Jew to hold the role, notes reasons for Arab political infighting, the origins of Arab dislike of Zionism, how land sales to Jews generate Arab jealousies, Jewish educational focus and the potential of the region of Palestine to support 4 million people.

For more than a century, Arab and Muslim leaders have expressed hatred for Jews, Zionism and Israel, although some have pointed internally for the failures of the Palestinian Arab national movement.

Primary sources, reputable scholarship and archival materials collectively show major communal (Arab-Jewish) socio-economic separation, factors that foreshadowed geo-spatial partition.

With intentioned ambiguity, Britain asserts that its goal in Palestine is not to make it wholly Jewish or subordinate the Arab population. Self-determination is not promised. Britain wants to remain an umpire between the communities. Naively, it thinks it can control communal expectations and keep the peace.

Using published archives, press conferences, speeches and numerous interviews, this compilation of quotations traces how official American views on Zionism and Israel have evolved over a century.

Annual reports to the League of Nations address the status and progress of the British Mandate for Palestine,

Ze’ev Jabotinsky argues that peaceful coexistence between Arabs and Jews in Palestine is impossible until Zionists demonstrate through strength that they are an irreversible presence in the Land of Israel.

Palestine’s High Commissioner Chancellor seeks to halt the Jewish National Home in favor of the Arabs. He fails to overcome the Zionist drive and Arab unwillingness to cooperate with his intentions.

Two letters detail how Arab peasants are sometimes swindled out of their lands by Arab land brokers and effendis, noting economic harm to them, and how they learn to avoid landlords and sell directly to Jewish buyers. Intra-Arab communal tension rises.

Palestinian Arabs’ own words, backed by the observations of British and Zionist officials, show that their awareness that their own people were helping the Zionist causes through land sales, often displacing Arab peasants.

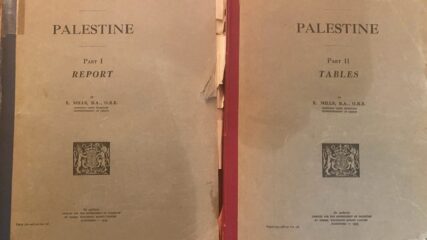

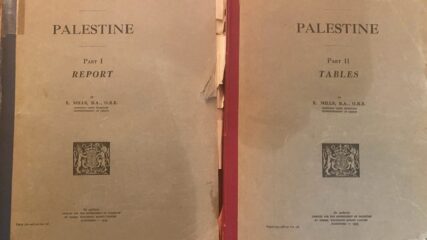

An invaluable glimpse at Palestine’s population: gaping socio-economic distances and vast communal differences between Muslims, Christians and Jews that set the strong preferences for separation of the populations.

Five Arab political parties sent a memorandum of protest to the British asking for a halt to Jewish immigration, a stoppage in Arab land sales to Jews,and a measure of self-determination. The British did not change their policies in these three areas. In 1939, they did severely limit Jewish land purchases and severely curtailed Jewish immigration.

Ben-Gurion recognized that Arab opposition to Zionism is a national feeling and that Palestinian Arab leadership had done little to help the majority impoverished peasant population.

After outbreak of communal violence, the British investigatory committee suggests partition of Palestine, seeking to create two states for two peoples.

Speculation again abounds whether a two state solution might be a seriously considered outcome to Palestinian-Israeli differences. A long history of its mention but not its implementation persists. Advocacy by external voices persists, but no one seems ready to make the critical political trade-offs required.

With more Arab sale offers than funds for purchases, Zionist leaders decide on strategic priorities and designate areas around Haifa, Jerusalem-Jaffa road, and the Galilee near headwaters of the

Jordan River.

This document was secured at the Central Zionist Archives in Jerusalem. Less than a year before Hitler invaded Poland, Arab leaders with an interest in Palestine are starkly disappointed that the the German government did not go to war against the Zionists in Palestine. The same leaders give the Zionist national builders high marks for their perseverance against terrorist bands in the Palestinian countryside. They worry that unless Arab states come to the Palestinians’ assistance, Palestine will be lost to the Zionists. A remarkable assessment for Palestinian Arab leaders and their supporters.

Pressure from Arab leaders in states surrounding Palestine, growing instability in the eastern Mediterranean, and a firm opposition voiced by the British High Commissioner in Egypt, Miles Lampson, caused the British to withdraw the idea of resolving the Arab-Zionist conflict with a two-state solution. Instead, heavy restrictions were imposed in 1939 on the growth of the Jewish National home. Coincidently this policy statement is issued, two days after Nazi Germany attacks Jewish, homes, businesses and synagogues, in what came to be known as Kristallnacht.

A description details the economic devastation caused by the 1936-1939 Arab disturbances in Palestine to the majority rural population. This followed the annually poor crop yields of the early 1930s, and the vast rural wreckage caused by WWI.

Mufti opposes Arab majority state in ten years contrary to wishes of a dozen key other Palestinian leaders. Mufti wants no Jewish political presence in Palestine whatsoever.

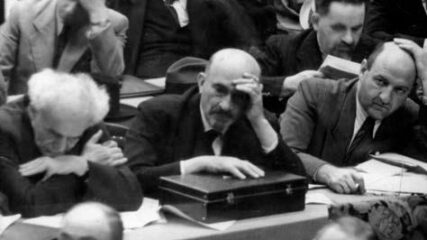

Zionist leaders—David Ben-Gurion, Chaim Weizmann and Eliezer Kaplan—learning of the British intent to limit severely the Jewish national home’s growth. Increasingly, they are also aware of the German government’s hostilities towards European Jewry.