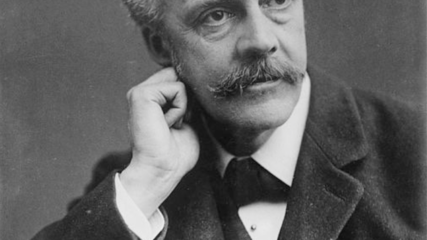

Balfour Declaration, 1917

The British Foreign Ministry promises to work toward a Jewish national home in Palestine with no harm to non-Jewish populations or to Jews living elsewhere who might want to support a Jewish home.

The British Foreign Ministry promises to work toward a Jewish national home in Palestine with no harm to non-Jewish populations or to Jews living elsewhere who might want to support a Jewish home.

A Zionist delegation to the Paris Peace Conference makes an effective, largely successful case for the League of Nations to incorporate a future Jewish national home into the British Mandate for Palestine.

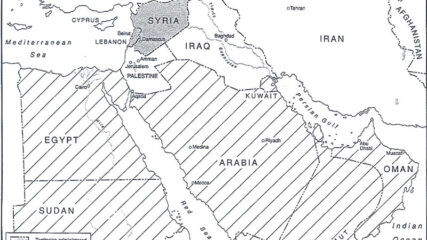

The post-WWI San Remo Conference allocates former Ottoman territories to Britain and France and recognizes Jewish self-determination in Palestine by adopting the language of the Balfour Declaration, decisions the League of Nations confirms two years later.

Primary sources, reputable scholarship and archival materials collectively show major communal (Arab-Jewish) socio-economic separation, factors that foreshadowed geo-spatial partition.

JNF meeting minutes and other statements show the strategic approach to Jewish land purchases throughout the British Mandate period.

Two letters detail how Arab peasants are sometimes swindled out of their lands by Arab land brokers and effendis, noting economic harm to them, and how they learn to avoid landlords and sell directly to Jewish buyers. Intra-Arab communal tension rises.

The sale of Zirin Village to the Jewish National Fund was collusively undertaken by a local Arab family through the British Courts in Palestine. The process intentionally avoided financial compensation to the resident Arab occupants.

Palestinian Arabs’ own words, backed by the observations of British and Zionist officials, show that their awareness that their own people were helping the Zionist causes through land sales, often displacing Arab peasants.

A report presented at the 18th Zionist Congress looks at the present and future of Jewish agricultural settlement and expansion in Mandatory Palestine, including the export market.

With more Arab sale offers than funds for purchases, Zionist leaders decide on strategic priorities and designate areas around Haifa, Jerusalem-Jaffa road, and the Galilee near headwaters of the

Jordan River.

A British investigation in 1939, before the release of that year’s anti-Jewish White Paper, finds that the area of Palestine was not promised to the Sharif of Mecca during World War I as part of a caliphate.

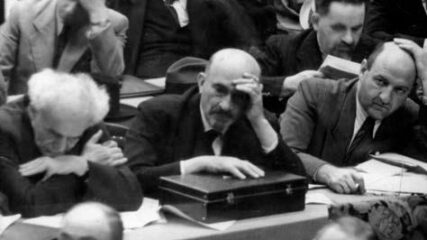

Zionist leaders—David Ben-Gurion, Chaim Weizmann and Eliezer Kaplan—learning of the British intent to limit severely the Jewish national home’s growth. Increasingly, they are also aware of the German government’s hostilities towards European Jewry.

Circumventing the existing law on prohibition of land sales to Jews, Palestinian Arabs are found selling lands regularly and furtively to Zionists.

The JNF estimated that up to 250,000 dunams (a dunam was a quarter of an acre) could be purchased if funds were available despite Arab opposition to sales and a steep rise in prices. By then, Jews owned 1.6 million dunams of land, with more than half of Palestine not owned by anyone.

After the June 1967 war, the Israeli government sent word through the United States to Egypt and Syria seeking to jump-start a peace process. Apparently no response was received.

Yigal Allon’s plan for handling the areas captured from Jordan during the just-completed Six-Day War reflects Israel’s previous border vulnerability and seeks a West Bank arrangement that is not a strategic or geographic threat.

Resolution 242 calls for Israeli withdrawal from unspecified captured territories in return for the right of all states to live in peace. It does not call for a full withdrawal. It is the basis for treaties with Egypt (1979) and Jordan (1994) and for PLO recognition of Israel (1993).

With less than three dozen Israeli settlements in the territories taken in the June War, the proposal is not for a vast settlement increase, but for economic, infrastructure, and industrial development of the areas.

The vast gulf in US and Israeli positions about Palestinian self-determination, the degree of withdrawal from the West Bank, and future borders is precisely stated. A year later at the end of the Camp David negotiations, Israeli and US views had not changed at all.

Sadat tells the Israeli people and world that he seeks a just and durable peace, which is not a separate peace, between Israel and Egypt. He equates statehood for the Palestinians as their right to return.

Five weeks after Egyptian President Anwar Sadat flew to Jerusalem in November 1977, to accelerate Egyptian – Israeli negotiations, Begin brought to President Jimmy Carter, Israel’s response to Sadat’s peace initiative: political autonomy for the Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. No Palestinian state was considered.

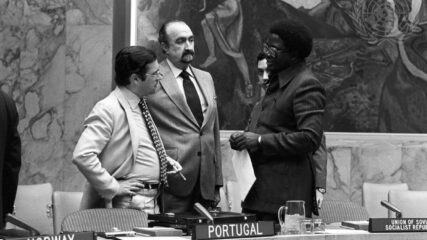

Carefully sandwiched between Jimmy Carter’s high-risk visit to Egypt and Israel and the signing of those countries’ peace treaty, the Carter administration allows the U.N. Security Council to deplore Israeli settlement building and demographic changes in Jerusalem.

This was the second UNSC Resolution within four months supported by the Carter administration condemning Israel’s settlement building in the territories. It too greatly angered the Israeli government and American supporters of Israel.

Showing its public opposition to Israeli actions in the lands taken in the June 1967 war, an area that the Carter Administration

wanted reserved for Palestinian self-rule, it ‘strongly deplores’ Israel’s settlement policies. Passage of the resolution three weeks

prior to the New York and Connecticut presidential primaries, cause many Jewish voters to vote in favor of Ted Kennedy

and not for Carter, helping to splinter the Democratic Party.