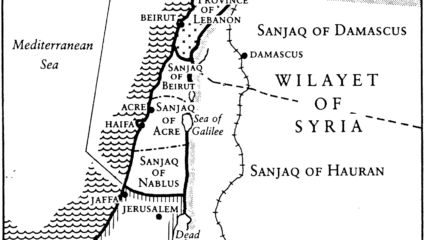

Assembled here are key sources that have shaped the modern Middle East, Zionism and Israel. We have included items that give texture, perspective and opinion to historical context. Many of these sources are mentioned in the Era summaries and contain explanatory introductions.

Major motivations for some Jews to choose Zionism included their failure to gain civic equality with their non-Jewish neighbors, and increasing outbreaks of rampant anti-Semitism. This account of the miserable economic situation of Jews in eastern Europe was another impetus for Jews to change their economic, political, and social condition through immigration.

Using published archives, press conferences, speeches and numerous interviews, this compilation of quotations traces how official American views on Zionism and Israel have evolved over a century.

Speculation again abounds whether a two state solution might be a seriously considered outcome to Palestinian-Israeli differences. A long history of its mention but not its implementation persists. Advocacy by external voices persists, but no one seems ready to make the critical political trade-offs required.

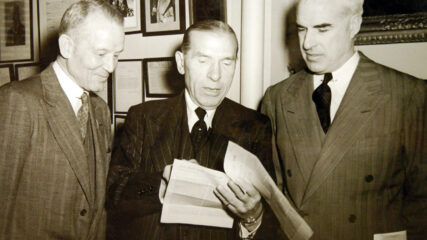

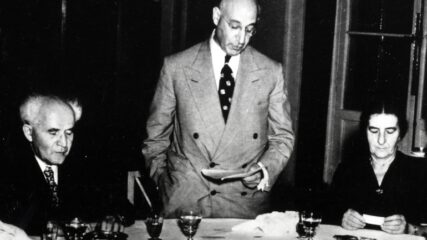

In New York, urging American (Jewish) support, Ben-Gurion proclaims the eventual establishment of a Jewish state.

In four days of sharply presented testimony and debate, the House evaluated the pros and cons of whether to endorse Jewish immigration to Palestine. Pressure from the Executive Branch not to pass such a resolution was heeded. According to Chief of Staff George Marshall “such a resolution would have adverse effects on the Moslem world.” This was the same argument that the State Department used in trying but failing to persuade President Truman in 1947 not to vote in favor of Palestine’s partition into Arab and Jewish states. The debate in the Congress took place more than a year before World War II ended in Europe. Fear of Arab state retaliation against the US never materialized because the US endorsed Jewish immigration to Palestine and a two state solution.

The report of a joint U.S.-British committee on the situation in Palestine and the fate of European Jewish refugees fails to offer solutions the British government will accept but does deliver vital data and insights on the situation between Arabs and Jews in the Land of Israel.

These Foreign Relations of the United States collections provide an ongoing, in-depth view at issues and conflict in the Middle East and the U.S.-Israel relationship from 1947 to 1978.

Fearing Communist penetration of the Eastern Mediterranean, Truman at the beginning of the Cold War defines the region as a sphere of US national interest.

Loy Henderson, Director of the Office of Near Eastern and African Affairs, U.S. State Department, to U.S. Secretary of State George Marshall

Writing two months before the U.S. voted at the United Nations in favor of Palestine’s partition into Arab and Jewish states, Henderson voices profound dislike for Zionism and a Jewish state. He advocates for cultivating positive relations with Muslim and Arab states. He is one of many at the State Department at the time who saw Zionism as contrary to American national interests.

No document better reveals the hostility which most Arab leaders and Arab states had in 1947 for Zionism and for a possible Jewish state. The Saudi King notes “that US support for Zionists in Palestine is an unfriendly act directed against the Arabs.” The King’s views were totally supported by US State Department officials including Loy Henderson and George Kennan who advocated strongly against Truman’s support of a Jewish state.

In March 1948, two months before Israel’s establishment, the US State Department sought to reverse the US vote in favor of partition for the creation of Arab and Jewish states in Palestine.

Upon admission to the U.N., Israeli Foreign Minister Moshe Sharett said, “It was

the consummation of a people’s transition from political anonymity to clear identity, from inferiority to equal status, from mere passive protest to active responsibility, from exclusion to membership in the family of nations.”

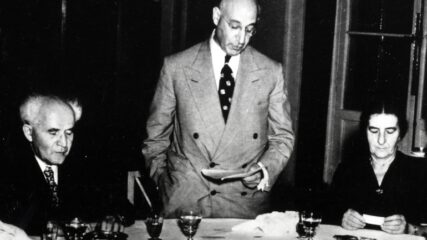

Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion and American Jewish Committee President Jacob Blaustein express a compromise in the American Jewish-Israel relationship: American Jews are excited and proud of Israel’s birth as a state but owe Israel no allegiance, and Israel does not speak for anyone but Israeli citizens.

Further reinforcing the Truman Doctrine, the US President promises military or economic aid to any Middle Eastern country resisting Communist aggression.

The Israeli ambassador to the United Nations delivers a detailed outline of events that will lead to war two days later.

President Johnson’s remarks became the philosophical outline for UN Resolution 242 passed in November 1967. Core to his view was that Israel would not need to return to the pre-1967 war borders, and that the territorial integrity and sovereignty of all states in the region should be protected.

Following the conclusion of the June 1967 War, the Israeli government sent word to Egypt and Syria seeking peace plan that was intended to jumpstart a peace process with Israel’s belligerent neighbors, Egypt and Syria. The messages were sent through the US, but no response was apparently received.

Resolution 242 calls for Israeli withdrawal from unspecified captured territories in return for the right of all states to live in peace. It does not call for a full withdrawal. It is the basis for treaties with Egypt (1979) and Jordan (1994) and for PLO recognition of Israel (1993).

Without any consultation with Jerusalem, Israel rejects US proposal for full withdrawal.

This volume of the U.S. government’s “Foreign Relations of the United States” series provides foreign policy documents on the Arab-Israeli conflict before, during and after the October 1973 war.

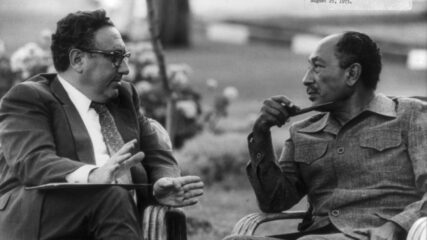

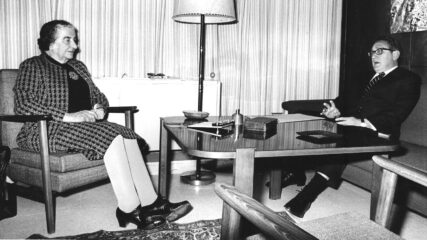

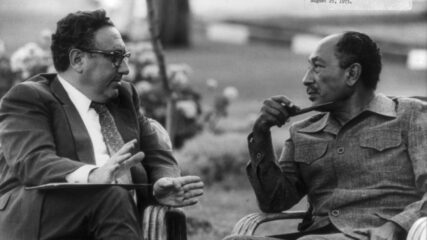

October 6, 2023, was the 50th anniversary of the outbreak of the October 1973 war. Six months prior, Egyptian President Sadat sent his national security adviser to meet with Secretary of State Kissinger to determine whether the U.S. would engage Egypt and Israel in serious mediation for a Sinai agreement, or a series of them, all focused on Israeli withdrawal and gradual acceptance of Israel. Kissinger did not take Sadat’s overtures seriously. Would American action then have avoided the October 1973 war? All informed analyses say no.

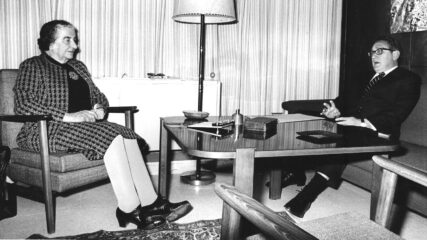

In carrying out research in the 1990s for Heroic Diplomacy: Sadat, Kissinger, Carter, Begin and the Quest for Arab-Israeli Peace, Routledge, 1999, I undertook 84 interviews with individuals who participated in the diplomacy.

The October 1973 war broke the logjam over whether diplomacy could unfold to kick off Arab-Israeli negotiations. Sadat used the 1973 war as an engine to harness American horsepower. In that he succeeded because U.S. Secretary of State Kissinger saw Sadat’s leaning to Washington not only as a chance to begin useful negotiations, but also of great significance to weaning the Egyptian president away from Moscow.

U.S. Secretary of State Kissinger failed to persuade Syrian President Assad to attend the December 1973 Geneva Middle East Peace Conference. Assad saw the proposed conference, which it was, a ruse to cover up a “pre-cooked” Israeli-Egyptian arrangement. Assad wanted no part of implicitly supporting any agreement where Israel’s legitimacy might be enhanced.