U.N. Security Council Resolution 465 on Jerusalem, Settlements and Territories, 1980CIE+

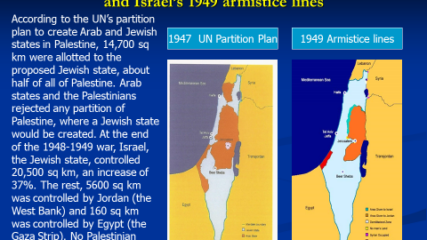

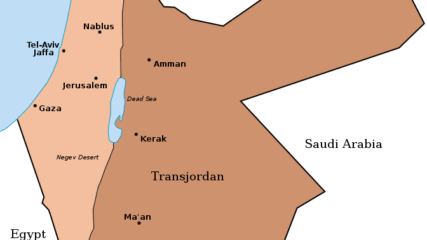

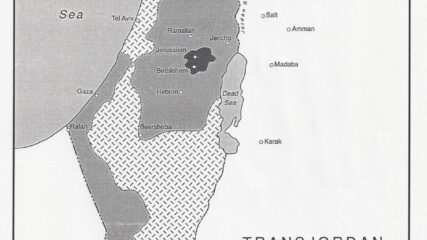

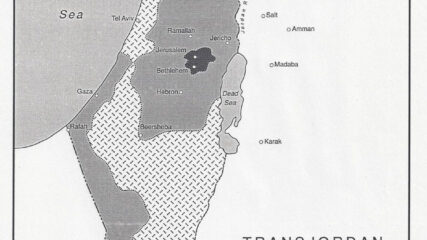

Showing its public opposition to Israeli actions in the lands taken in the June 1967 war, an area that the Carter Administration

wanted reserved for Palestinian self-rule, it ‘strongly deplores’ Israel’s settlement policies. Passage of the resolution three weeks

prior to the New York and Connecticut presidential primaries, cause many Jewish voters to vote in favor of Ted Kennedy

and not for Carter, helping to splinter the Democratic Party.