Israel-Egypt Separation of Forces Agreement, 1974CIE+

The U.S. mediates an agreement separating forces in Sinai after the October 1973 war. Egyptian and Israeli generals will negotiate additional details.

The U.S. mediates an agreement separating forces in Sinai after the October 1973 war. Egyptian and Israeli generals will negotiate additional details.

The US promises to implement an Egyptian-Israeli disengagement agreement and have the Suez Canal cleared. Israel sees eventual repopulation of Suez Canal cities as a sign that Egypt will not go to war again soon.

President Ford promises that the US will give “weight” to any future Israeli peace agreement with Syria that Israel should remain in the Golan Heights.

Cairo and Jerusalem agree to additional Sinai withdrawals, demilitarized zones, limited force zones and, importantly, placement of US civilians in Sinai to monitor observance of agreement.

The US promises coordination with Israel on resumed negotiations, not to negotiate or recognize

the PLO until it recognizes Israel’s right to exist, and accepts UNSC Resolutions 242 (1967) and 338 (1973).

Led by USSR and Arab states, Zionism is labeled as racist; the resolution is revoked in 1991.

For the first time a US State Department official states the “legitimate interests of the Palestinian Arabs must be taken into account in the negotiating of an Arab-Israeli peace.”

Outlining an Arab-Israeli settlement, the Brookings report calls for Israel to withdraw to “almost the pre-June War borders” and for “extensive Palestinian autonomy.” The Carter administration embraces the report for its foreign policy.

With candor, Israeli Foreign Minister Allon tells Secretary of State Vance that the Israeli Labor government would under no circumstances negotiate with the PLO until it gave up terrorism, recognized UNSC 242, and unequivocally accepted Israel’s right to exist. Only in 1993, did the PLO accept these premises, Sixteen years had then passed while Israel built settlements virtually without restraint in the territories.

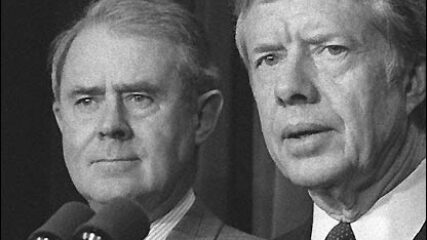

This first Carter-Rabin meeting was unpleasant at best. Rabin would not turn over Israel’s negotiating prerogatives to the US; Carter publicly told Israel that it might have to return to the June 1967 borders. Carter said Rabin was like a “dead fish.” and Rabin said that he felt ‘cornered by Carter.” His administration was interested in carving out the West Bank for Palestinian political expression even before the PLO was prepared to accept Israeli legitimacy. And Israel was not prepared to withdraw from the West Bank, a position also held by Menachem Begin.

Carefully stated, Carter says that there should be a homeland for the Palestinian refugees. He is the first US president to assert the need for a place for the Palestinians and for Israel’s right to exist in peace.

In their first meeting, Anwar Sadat and Jimmy Carter have a vividly detailed exchange about negotiations between Israel and Arab parties, particularly Egypt.

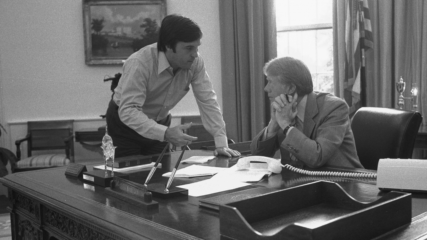

When the Carter Administration entered office in 1977, an early foreign policy priority was to kick-start Middle East negotiations. In this Policy Review Committee Meeting, Carter’s staff proposed a negotiating outcome that would pass through a conference, including the withdrawal of Israel’s forces to almost the 1967 borders, bringing the PLO into talks as Palestinian representatives, all the while seeking to uphold Israel’s security requirements.

This meeting was the only one between U.S. President Carter and Syrian President Assad during the Carter administration. Carter wanted to learn Assad’s requirements for an agreement with Israel. Assad doubted that the Saudis would join this process. In the end, Assad made it clear that he was not rushing into an agreement with Israel, even if asked by the United States. Carter acknowledged knowing little about the Palestinian refugee issue and said the U.S. was committed to the security of Israel.

Prime Minister-elect Begin rebukes President Carter’s assertion that Israel will need to withdraw from almost all the lands Israel secured in the June 1967 war, especially Jerusalem and the West Bank. Begin is adamant opposed to dealing with the PLO. Begin refuses to relinquish Israeli decision-making to US preferences or dictates. These fundamental policy disagreements will remain unresolved between Begin and Carter for the duration of Carter’s presidency, and years after.

Hamilton Jordan, Carter’s chief political adviser, warned the president to halt the administration’s anti-Israeli actions. Nonetheless, they continued to diminish Carter’s support among American Jews through the 1980 re-election campaign.

Begin tells Carter that Judea, Samaria (the West Bank) and the Gaza Strip will not be placed under foreign sovereignty; likewise, these areas will not be annexed, leaving them open for possible negotiations.

After his surprise electoral victory in May, Prime Minister Menachem Begin traveled to Washington to establish a rapport with President Carter. While this initial meeting was cordial, each met the other’s stubbornness, a characteristic that would keep their relationship respectful but acrid for years to come.

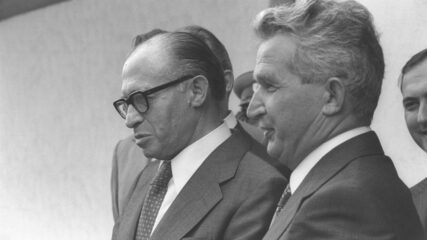

Unknown to the Carter administration and one month before it issued the US-Soviet Declaration to convene an international Middle East Peace Conference, Prime Minister Begin tells the cabinet that he learned from the Rumanian president that Sadat wishes to have Israeli and Egyptian representatives meet in secret talks. That bi-lateral Dayan -Tuhami meeting takes place on September 16. Begin refers to advanced drafts of proposed treaties between Israel and each Arab state; he presents details about Rumanian Jewish immigration to Israel.

The vast gulf in US and Israeli positions about Palestinian self-determination, the degree of withdrawal from the West Bank, and future borders is precisely stated. A year later at the end of the Camp David negotiations, Israeli and US views had not changed at all.

In two meetings at the White House, the Syrian foreign minister insists on the PLO’s presence at a regional peace conference and wins U.S. support for some kind of Palestinian “entity.”

Naively, the Carter Administration believes that a conference with the USSR would start comprehensive negotiations; instead, the fear of Moscow’s engagement helps drive direct Egyptian-Israeli talks.

After brutally frank and caustic meetings between Israeli Foreign Minister Dayan and President Carter, the US relents to Israeli demands that a peace conference be only an opening for direct talks.

Common to both the Labor Party and to Begin’s government was a fear that the US would pressure Israel into unwanted concessions and deny Israel its right to sovereign decision-making. It was a concern that Dayan expressed in this October 1977 meeting, and one that he would articulate on several occasions during the Camp David negotiations.