U.S.-Israel Joint Statement on Strategic Cooperation, 1996CIE+

President Clinton and Prime Minister Peres agree to deepen cooperation between their countries through regular consultation in all economic, political, military spheres.

President Clinton and Prime Minister Peres agree to deepen cooperation between their countries through regular consultation in all economic, political, military spheres.

With Israeli-Palestinian talks in a hapless state, President Clinton rejuvenates them. In the Arafat-Netanyahu agreement Israel shares Hebron, with the CIA playing a role in West Bank security.

After failing to have PLO leader Yasser Arafat and Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak reach an understanding at Camp David in mid-2000, President Bill Clinton offers a U.S. view of a final-status agreement near the end of his term.

In the midst of severe Palestinian-Israeli clashes, a committee led by former U.S. Sen. George Mitchell concludes, as had many previous investigations, that the two communities fear and want to live separately from each other. From the report flows the EU-U.N.-U.S. commitment to a two-state solution suggested in the 2003 Roadmap for Peace.

CIA Director George Tenet proposes a cease-fire to stop vicious Palestinian-Israeli violence that carries on for four more years. The plan seeks to restore Palestinian-Israeli security cooperation, end incitement, arrest militants and establish mechanisms for accountability through the U.S.

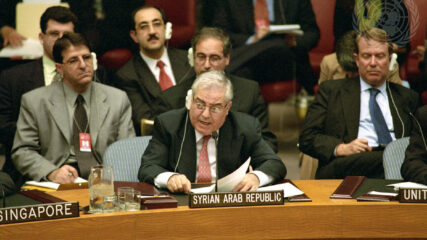

This is the first U.N. resolution to call for “two States, Israel and Palestine, to live side by side within secure and recognized borders.”

President Bush castigates PLO leader Arafat for support of terrorism and condemns Palestinian groups that “seek Israel’s destruction.” He also suggests that Israel economically support a viable Palestinian state.

As a negotiating plan it seeks an end to the conflict with reciprocal performance objectives. Israel accepts the plan with some reservations; Hamas rejects it out of hand. The plan is not enacted.

President Bush outlines view of Palestinian-Israeli settlement with Israeli Prime Minister: two state solution, borders to take into account changes in territories since 1967 War, and refugee resettlement in a future Palestinian state.

Prime Minister Sharon unilaterally withdrew Israeli military and civilian forces from the Gaza Strip in August 2005. Sharon sought to ensure Israel’s Jewish and democratic essence by getting out of the lives of the Palestinians. Instead Hamas used the territory to kill Jews and degrade Israel morally. Two decades later what would Sharon have said about trusting your neighbor unilaterally?

Israeli Prime Minister Olmert and Palestinian leader Abbas meet near Washington to kick-start negotiations by implementing previous promises; the U.S. is to judge performance to see if a treaty can result. It does not.

Delivering the third address by a U.S. president to the Knesset, George W. Bush celebrates Israel’s 60th birthday by emphasizing the enduring U.S.-Israel relationship based on shared values.

Barack Obama, while seeking to improve America’s image by urging an end to violence and stereotypes, emphasizes the need for a two-state Israeli-Palestinian solution as part of a reset of U.S. relations with the Muslim world. His advocacy of soft power distinguishes his administration from George W. Bush’s use of force. Nine years later, Donald Trump’s secretary of state, also in Cairo, heavily criticizes the Obama soft-power approach.

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu endorses the evolution of a Palestinian state, stipulating that it must be demilitarized. He does not rule out a halt to settlement activity but says Palestinian refugees will not be resettled inside Israel’s borders.

Focusing on the Arab Spring and Palestinian-Israeli negotiations, President Obama seeks democratic reform in the region and advocates two states for two peoples based on the 1967 lines with land swaps.

Defense Secretary Leon Panetta’s speech is typical of high American officeholders in summarizing the U.S.-Israeli relationship. Panetta affirms an unshakable relationship, support for Israeli security and the need for a negotiating progress.

Vice President Joe Biden emphatically tells a rabbinic group in Atlanta, “unambiguously, were I an Israeli, were I a Jew, I would not contract out my security to anybody, even to a loyal, loyal friend like the United States.”

Building on a collaborative relationship of over 50 years, the US once again affirms its strategic commitments to Israel through an additional “Security Cooperation Act.” The agreement bolsters American military and financial aid to Israel.

Biden’s is seized by Iran’s nuclear weapons program, and its continued support of terrorist organizations, like Hezbollah and Hamas; they endanger Israel and the world. Golda Meir told him. “Israel’s secret weapon; it has no place to go.”

In Jerusalem, Obama affirms the bonds in the U.S.-Israeli relationship, praises Israel’s democracy, and calls for Israelis to support a democratic Palestinian state and Palestinians to recognize Israel as a Jewish state.

Kerry reaffirms that the US-Israeli relationship as an “unshakable bond” and calls for a two-state solution. He promises that the US will “never allow” Iran to gain a nuclear weapon.

As part of the US negotiating team, Indyk enumerates why talks faltered after nine months. He asserts Israeli settlement activity undermined Palestinian trust for Israel. He also blames Palestinian indecision.

Following two weeks of Israeli-Hamas fighting, it calls for a cease-fire, and for a “lasting solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict by peaceful means.” The Hamas-Israeli war occurs again in 2013-2014.

The U.S. president announces a coalition of countries to fight the Islamic State in Syria and Iraq. His plan calls for limited U.S. military action with supplies provided to others fighting on the ground.